Your Daybill

Info

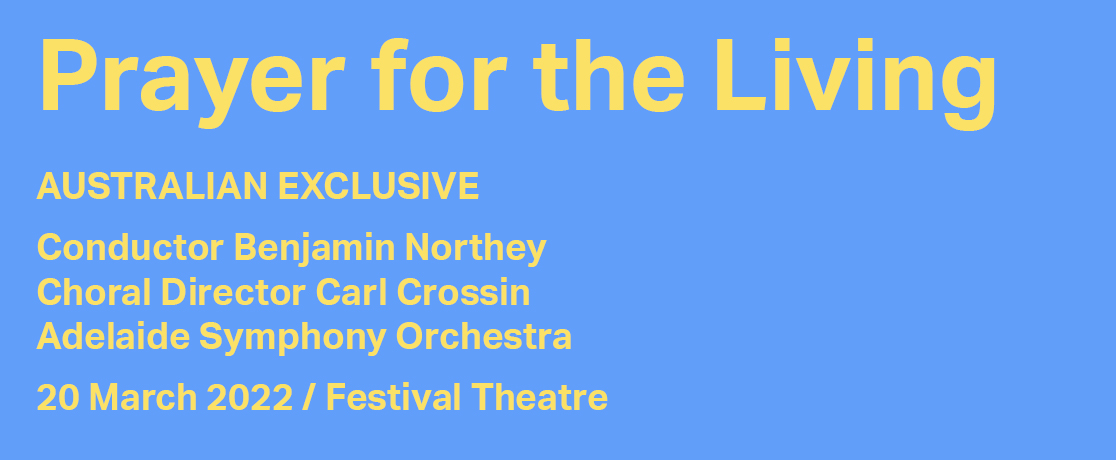

Credits

creative team

Benjamin Northey, conductor

Carl Crossin, choral director

Stacey Alleaume, soprano

Nicholas Jones, tenor

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra

VIOLINS

Cameron Hill**

Acting Concertmaster

Shirin Lim**

Acting Associate Concertmaster

Michael Milton*

Acting Principal 1st Violin

Alison Heike**

Principal 2nd Violin

Lachlan Bramble~

Associate Principal 2nd Violin

Janet Anderson

Ann Axelby

Louise Beaston

Minas Berberyan

Gillian Braithwaite

Julia Brittain

Hilary Bruer

Nadia Buck

Elizabeth Collins

Jane Collins

Judy Coombe

Belinda Gehlert

Danielle Jaquillard

Zsuzsa Leon

Alexis Milton

Emma Perkins

Alexander Permezel

Paris Williams

VIOLAS

Justin Julian**

Linda Garrett~

Guest Associate

Martin Alexander

Lesley Cockram

Anna Hansen

Rosi McGowran

Carolyn Mooz

Michael Robertson

Cecily Satchell

CELLOS

Simon Cobcroft**

Sharon Grigoryan~

Guest Associate

Sarah Denbigh

Christopher Handley

Sherrilyn Handley

Gemma Phillips

David Sharp

Cameron Waters

DOUBLE BASSES

David Schilling**

Jonathon Coco~

Jacky Chang

Harley Gray

Belinda Kendall-Smith

Sean Renaud

FLUTES

Geoffrey Collins**

Lisa Gill

PICCOLO

Julia Grenfell*

OBOES

Renae Stavely~

An Nguyen

COR ANGLAIS

Peter Duggan*

CLARINETS

Dean Newcomb**

Darren Skelton

BASS CLARINET

Mitchell Berick*

BASSOONS

Mark Gaydon**

Chris Buckley

CONTRA BASSOON

Leah Stephenson*

Acting Principal

HORNS

Sarah Barrett~

Emma Gregan

Philip Paine*

Timothy Skelly

TRUMPETS

David Khafagi**

Martin Phillipson~

Gregory Frick

TROMBONES

Colin Prichard**

Ian Denbigh

Charlie Thomas

BASS TROMBONE

Amanda Tillett*

Guest Principal

TUBA

Karina Filipi*

Guest Principal

TIMPANI

Andrew Penrose*

PERCUSSION

Steven Peterka**

Sami Butler~

HARPS

Lucy Reeves**

Guest Section Principal

Carolyn Burgess

CELESTA

Jamie Cock*

Guest Principal

** denotes Section Principal

~ denotes Associate Principal

* denotes Principal Player

The Choir

comprising members of

Elder Conservatorium Chorale – music director & conductor, Carl Crossin OAM

Graduate Singers – music director & conductor, Karl Geiger

Sopranos

Nicola Bevan

Sarah Bleby

Millicent Brake

Susan Brooke-Smith

Abbey Bubner

Lisa Catinari

Emma Chesterman

Verity Colyer

Katelyn Crawford

Lauren Driver

Michaela Eaton

Jackie Eldridge

Ciara Ferguson

Alison Fleming

Alexandra Fowler

Nadia Gencarelli

Gianna Guttilla

Alison Hardy

Leyang Hong

Imala Konyn

Katharine Lahn

Nicky Marshall

Sarah O'Brien

Amelia Price

Cherie Surman

Imogen Tonkin

ALTOs

Phuong-Nhi Banh

Marley Banham

Danae Bettison

Ruby Butcher

Riana Chakravarti

Lily Coats

Georgina Gold

Alison Hansen

Lauren Holdstock

Elliette Kirkbride

Carrie Lam

Cassie Lee

Joeryn Loh

Monique Lymn

Hamish Madden

Isobel Martin

Cathryn McDonald

Susan Murdoch

Stephanie Neale

Melinda Pike

Katherine Samarzia

Melanie Sandford-Morgan

Lisa Schulz

Chia Tu Seo

Genevieve Spalding

Lucy Stevens

Casey Sullivan

Yong Huey Teoh

Deborah Tranter

Madeline Turnbull

Elinor Warwick

Karen Watson

Karen Yau

Darcie Yelland

Bofan Zhang

Michelle Zweck

TENORs

James Donlan

Darren Lutze

William Madden

Lou McGee

Tommy Ng

Jack Overall

Jo Pike

Gina Sinclair

Billy St. John

Liam Taylor

Craig Weatherill

Rhys Williams

Graham Yuile

BASSes

Stuart Carter

Damien Day

Jason Geddie

Scott Gunn

Andrew Heitmann

Paul Henning

Nikolai Leske

Andrew Moschou

Timothy Pietsch

Neil Piggott

Tommy Raets

Andrew Raftery

Mark Roberts

David Rohrsheim

Mark Sales

Tim Sheehan

David Shields

Chris Steketee

Joshua Sweaney

Lachlan Symonds

Tom Turnbull

Ian van Schalkwyk

Joel Wilson

Matthew Winefield

Bryce Winter

Program

Pēteris Vasks (born 1946)

Lūgšana mātei (Prayer for the Mother)

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

Psalm 129

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Deux mélodies hébraïques, No 1. Kaddisch

Boulanger

Vielle prière bouddhique (Old Buddhist Monk)

Vasks

Dona nobis pacem

Interval

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

Gloria

Gloria in excelsis Deo

Laudamus te

Domine Deus, Rex caelestis

Domine Fili unigenite

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris

Program Note

By Alan John

Latvia’s Pēteris Vasks, like Arvo Pärt, Henryk Górecki and John Tavener, is a former acolyte, turned heretic, of the avant garde orthodoxy of the 60s and 70s. Today the composers are all put in a box with the rather silly name tag ‘holy minimalists’, but Vasks’s pragmatic Baptist faith is a world away from, say, Tavener’s esoteric mysticism. What they do have in common is a belief that profound spirituality can be expressed through sparse and apparently “simple” means.

Lūgšana mātei or Prayer for a Mother (originally given the more Soviet-friendly title “Cantata for Women”) is a transitional work from 1978, and still maintains vestiges of aleatoric (random, performer-driven) techniques. The final overlapping improvised sounds of maternal/baby babble is a rare example of a gesture that’s both utterly commonplace and strikingly original. It’s so universal that it touches us every bit as directly as do the soaring, if more conventional sounding, solos for clarinet and soprano. The text, by dissident Latvian poet Imants Ziedonis, is arguably a little tainted these days by a male gaze that seems to confine a woman’s destiny to giving birth. However, as an empathetic paeon to mothers and children in adversity, as well as joy, the music is transcendent.

Dona nobis pacem, from 1996, is more typical of the composer’s choral output. It’s strictly model (oscillating between the old Aeolian and Phrygian church modes) so were you to play it on the organ there would not be a single ‘black note’. Avoidance of chromaticism is often assumed to reflect meditative calm, but this work sustains a great deal of tension over its 13 or so minutes. The polyphony is straightforward and more reminiscent of the 12th century Notre Dame school than of later Renaissance composers. The smaller and smaller divisions of triple time employed in the accompaning parts also hark back to late medieval practice, but here the effect is accumulative rather than decorative. The simple plea for peace rises then falls, in various guises, before settling on one ‘hero’ melody. This melody, as in a Bruckner Adagio, seems to set off on a perilous climb to the heavens, doesn’t quite make it, regroups for a second attempt and gets there, although the expected epiphany is veiled by the kind of high string clusters you find in Pärt. The stillness of the coda hovers between resignation and exhaustion, as if the angelic promise of peace on earth is eternally unfulfilled. The composer speaks movingly of the dilemma, and offers a small source of hope:

I get the sense that events in the world slowly cause a loss of foundations under our feet. God give that the horrors that we see in Ukraine and the Middle East can be extinguished, because otherwise we will be incinerated in this fire. Each of us can do something to stop this craziness. Let us speak good and loving words to one another, because they have much strength. Every smile, every word that is spoken with love, every caress – believe me, that is numerous strength.

Pēteris Vasks

In 1913, Diaghilev brought the St Petersburg Opera to Paris and London to premiere a newly completed version of Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina. Stravinsky had been commissioned to restore and re-orchestrate but, up to his ears in the imminent Rite of Spring, he sub-contracted out to his new friend and champion, Maurice Ravel. Ultimately, the work of both composers was largely lost when the fickle impresario caved in to the demands of his star bass, Chaliapin (who preferred the Rimsky Korsakov arrangement!), but from the wreckage came an unexpected jewel. Alvina Alvi, one of the company’s principal sopranos, had admired Ravel’s setting of a Yiddish text in his Chansons populaires, and she commissioned him to arrange two traditional melodies, one sacred and one secular, in what became the Deux mélodies hébraïques from 1914.

The first of these is the famous Kaddish, whose text in Aramaic is one of the most important prayers in Jewish liturgy, and which in its extended form is an expression of profound personal mourning. Ravel sets the shorter Chatzi Kaddish, and strangely the jury is still out on whether it is an authentic cantor melody. Presumably he transcribed it from the voice of its commissioner and first performer, but the spirit of the setting is deeply respected by Jews to this day and suggests that Ravel may have spent some time listening in synagogues. The soloist’s ecstatic melismas against a largely still, bell-like texture create one of the most haunting pieces of sacred music ever composed, ironically from an avowed atheist. The tenor is accompanied here by the composer’s own orchestration (1919) of the original piano part.

Lili Boulanger’s legacy as a composer is always in danger of being overshadowed by the heartbreaking circumstances of her untimely death from intestinal TB, while war still raged in March 1918. At her funeral, poet and critic Camille Mauclair summed up what has become an enduring portrait of her as a wan, self-sacrificing femme fragile: “This is a story of a departed child of twenty-four years who almost never ceased suffering, and the story of a genius, who revealed herself in this fragile and charming body.”

The Boulanger sisters, daughters of a Russian princess, were, in fact, far from shrinking violets. Both gifted musicians and composers, they competed with each other mercilessly for the coveted Prix de Rome once it was declared open to women in 1903. On her third attempt, Nadia was a technical runner up in 1908, then Lily entered but pulled out sick in 1912, before becoming the first female winner (aged only 19) the following year. Nadia, bowing to her younger sister’s prodigious talent, gave up writing music, but later became the most influential composition teacher of the century.

The lucky winner was meant to enjoy creative space during their all-expenses-paid stay in Rome’s Villa Medici. Lily, however, hardly had time to enjoy the hastily thrown together women’s bathroom facilities before heading back to France to support her comrades from the musical world who had enlisted. Her efforts went way beyond sock-knitting and soothing the brows of the wounded. With her sister, she rallied the venerable frames of Fauré, Saint-Saëns and Widor and founded a charity for ex-musicians at the front and wrote and distributed a servicemen’s publication focused on music. She became passionately engaged in raging debates about whether supporting French culture meant throwing Beethoven and Schoenberg out with the Wagnerian bathwater. All the while, ill as she was, she was completing her greatest works: three gigantic orchestral psalm settings and the remarkable Old Buddhist Prayer.

Muscular, vehement and seething with dark rage, Psalm 129 is largely set for male chorus, with women providing a wordless ‘halo’ towards the end. The thick, low register wind writing suggests ancient shawms and shofars but is also prescient of Stravinsky and Messiaen. A cry from those dispossessed by war, this setting could have been a powerful public statement in those dark days, but it was never performed until 1921. Today the mental image of a sea of people forced to survive on food grown on the rooftops of their makeshift shelters brings to mind the plight of refugees from Syria, Sudan or Myanmar.

The beautifully orchestrated Vieille prière bouddhique (Old Buddhist Prayer) is blissfully benign, if tinged with sadness. With its ambiguous, notionally Asiatic modality and flute arabesques, it doesn’t stray too far from the kind of French ‘orientalism’ found in her contemporaries Debussy, Roussel and Delage. What is truly audacious, though, is the choice of text, given that this was a time when French troops were openly defying their commanding officers in protest against the obscenely futile loss of life in the trenches. Debussy’s response was the jingoistic Ode à la France. Radically, Boulanger gave (imagined) public voice to non-violent, pan-global sentiments. The words came to her via another pioneering woman of the time, Suzanne Karpelès, a family friend and established French scholar of Sanskrit, Pâli, Tibetan, and Nepalese, who later became famous as a cultural diplomat in Cambodia and Laos. Her translation purposefully adapted the Pâli text to embrace a less specifically religious and more generally humanist, universalist outlook.

As active as she was in the defence of France, Boulanger's hatred for war is evident is this diary entry:

Naval battle in the North Sea between the English and the Germans–what horror!–without result other than innumerable atrocities, suffering–oh! It is too painful.

Lili Boulanger,

in a diary entry dated 3 June 1916

Painful too is the fact that she herself died before being able to experience peace and the riches of French music in the following decades.

Nearly 60 years after his death, many are yet to reconcile the ‘two sides’ of Francis Poulenc. The question is still posed, “Can the mind that produced Les Biches really be responsible for some of the greatest and most sincere sacred music ever composed?” At least now his sexuality is openly acknowledged (for years music critics opted for coded descriptives like ‘snappy dresser’, ‘waspishly witty’, ‘urbane’ and the like), but there still seems to be a level of bewilderment around his being openly gay and devoutly Catholic.

His wonderful setting of the Gloria from the Latin mass was premiered in 1961, and belongs to the extremely productive last decade of his life, which also saw the creation of his operatic masterworks, Dialogues des Carmélites and La voix humaine, and the closest he came to a requiem setting, the Sept répons des ténèbres. Poulenc characteristically quipped that, together with his Stabat Mater of 1950, the trilogy of big liturgical works might “spare me a few days in Purgatory if I narrowly avoid going to hell”.

Paid for by a Koussevitzky Foundation commission, but apparently conceived well in advance of it, the Gloria’s first outing in Boston under Charles Munch was a great success. From its magnificent, swaggering opening to its serenely humble Amen, this tuneful, often rambunctious and earthy expression of faith, so devoid of po-faced religiosity, is attractive on one hearing. It’s not surprising that the piece has remained a hit with performers and audiences alike for so long.

The predominant musical intellectuals of the day, however, treated it as an embarrassment. The European premiere under Georges Prêtre prompted some to turn up their nose at a piece that contained so much unashamedly happy music (actually in the key of C major and G major for long stretches!). A BBC memo was circulated advising against putting any effort into British performances or broadcasts of this shallow and vulgar setting of words “which are of great dignity, significance and familiarity”.

It’s true the stressing of the Latin syllables sounds odd to English ears (although “Gloria in excelsis Deo” is consistent with French practice) and on occasion it’s almost flippant (“Lauda…Lauda…Laudamus Te”), but Poulenc makes you hear the words afresh, and is supremely confident that worship takes many forms. He said that the now famous second movement was inspired by seeing a bunch of Benedictine monks playing a game of soccer. It’s a work that can jolt you with unexpected blurting fortissimo augmented ninth chords, not out of place in Duke Ellington, while also managing to explore mysterious realms of the soul, especially in the ravishing writing for solo Soprano.

For all his brilliance at dinner parties, Poulenc was a private depressive. The negative comments, about what he believed was a major work, hurt him and prompted a bout of his habitual self-criticism and doubts about how history would view his achievements:

After all, my music is not that bad, even though sometimes I wonder why I go on, and for whom? Do understand that I’m not jealous (there’s room for everybody), but when I read that Messiaen and Jolivet are the two important composers, I question myself.

Francis Poulenc, in a letter to Henri Hell,

quoted in Poulenc: A Biography by Roger Nichols

Two years later, a heart attack killed him. Today the composer who, while mindful and appreciative of the prevailing trends, embraced the challenge of writing tonal music that was both new and good, is being reassessed, and his music increasingly loved.

Texts & Translations

Prayer for a Mother

Poem by Imants Ziedonis

Peace to the mother’s breasts,

Where the child will nurse.

Peace to the mother’s heart under them.

Peace to those who will blossom, peace to those who will wither,

And to those who will remain barren.

Peace to those who do not yet have, but will.

And peace to those who have already received.

Peace to those who did not meet us in the world.

But very much waited and believed.

Translated by Amanda Zaeska. Reprinted with kind permission of the Latvian Music Information Centre.

Psalm 129

Since I was young, they have bitterly oppressed me

Yet they have not beaten me.

Their ploughmen have ploughed my back,

Cutting deep long furrows.

Let all those that hate us be defeated and put to shame!

Let them be like grass grown on rooftops,

That withers before it ripens

Giving the reaper a pitiful harvest.

Let no one who passes them say,

“God’s blessing is upon you”

Kaddish

Magnified and sanctified be His great name throughout the world that He has created according to His will. May He establish His kingdom during the days of our life and our days and the life of the entire House of Israel speedily and soon, and let us say Amen.

(Here normally comes a congregational response, which is missing from Ravel's setting).

Blessed and praised, honoured and extolled, lauded and glorified, acclaimed and adored be the name of the Holy One blessed be He, beyond all blessings, hymns, praise and consolation that are uttered in this world, and let us say Amen.

Approximate translation by Boaz Tarsi, for the words of the Kaddish that Ravel set to music.

Old Buddhist Prayer

Let everything that breathes -- let all creatures everywhere,

all the spirits and all those who are born,

all the women, all the men,

Aryans, and non-Aryans,

all the Gods and all the people,

and those who are fallen:

in the East and in the West, of the North and the South,

Let all those beings which exist --

without enemies, without obstacles,

overcoming their grief and attaining happiness,

be able to move freely, each in the path destined for them.

Adapted and translated (into French) from the original Pâli by Suzanne Karpelès.

Dona nobis pacem

Grant us peace.

Gloria

I

Glory to God in the highest

And on earth peace, goodwill to all people.

II

We praise you; we bless you;

We give thanks to you for your great glory.

III

Lord God, heavenly King, Almighty Father.

IV

Lord, the only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ.

V

Lord God, Lamb of God

Who takes away the sins of the world,

Have mercy on us. Receive our prayers.

VI

You who sit at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us.

Only you are holy, only you are Lord. Only you are most high.

Jesus Christ, the Holy Spirit in the glory of God the Father. Amen.

Benjamin Northey

Conductor

Since returning to Australia from Europe, Benjamin Northey has rapidly emerged as one of the nation’s leading musical figures. He is currently the Principal Resident Conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and was appointed Chief Conductor of the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra in 2015.

His international appearances include concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, the Mozarteum Orchestra Salzburg, the Hong Kong Philharmonic, the National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia, the Malaysian Philharmonic and the New Zealand Symphony and Auckland Philharmonia.

He has conducted L'elisir d'amore, The Tales of Hoffmann and La sonnambula for State Opera South Australia and Turandot, Don Giovanni, Carmen and Cosi fan tutte for Opera Australia.

Limelight Magazine named him Australian Artist of the Year in 2018. In 2022, he conducts the Christchurch and New Zealand Symphony Orchestras and all six Australian state symphony orchestras.

Carl Crossin

Choral Director

Carl Crossin is widely respected as one of Australia’s leading choral conductors. He is currently Associate Professor of Music at the Elder Conservatorium of Music where he has served in several leadership positions, including Head of Vocal, Choral & Conducting Studies and Director of the Conservatorium.

Carl recently stepped down as Artistic Director and Conductor of the multi-award-winning Adelaide Chamber Singers, having founded and led the choir to a position of national and international prominence and respect from 1985 - 2021. Carl has guest conducted leading choirs throughout Australia, and has enjoyed a long association with Australia’s two national youth choirs – Gondwana Chorale and the National Youth Choir of Australia. He has also toured nationally and internationally with both choirs.

In 2007, Carl was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for his services to music, and was inducted into the South Australian Music Hall of Fame in 2021.

Stacey Alleaume

Soprano

Renowned for her voice of remarkable beauty, warmth, character and expression, Australian-Mauritian soprano Stacey Alleaume has established herself with an exciting operatic career ahead.

Stacey’s artistic development has been supported by grants and scholarships including the 2016 Dame Joan Sutherland Scholarship for outstanding Australian operatic talent. She was also invited into Opera Australia’s Moffat Oxenbould Young Artist Program.

In her first year as a Young Artist, Stacey made three role debuts: Micaëla in Carmen, Leïla in The Pearl Fishers and Alexandra Mason in The Eighth Wonder. Since then, she has shone in principal roles including Fiorilla (Il turco in Italia), Sophie (Werther), Gilda (Rigoletto), Valencienne (The Merry Widow), Susanna (Le Nozze di Figaro) and Violetta (La Traviata).

Stacey made her European debut in 2019 performing Gilda in Rigoletto at the Bregenzer Festspiele and returned in 2021 to reprise the role. She has also covered the title role in Lakmé, and sang the role of Frasquita in Carmen, both for The Royal Opera House Muscat.

Nicholas Jones

Tenor

Brilliant young tenor Nicholas Jones won the Green Room Award for his portrayal of David in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg for Opera Australia. He was nominated for a Helpmann Award for this same role.

Other appearances for the national company have included Tamino in The Magic Flute, Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Michael Driscoll in the world premiere of Whiteley and Tony in West Side Story. For State Opera South Australia, he has sung Fish Lamb in Cloudstreet and Tom in Christina’s World; for Pinchgut Opera – Mercury/Thespis in Platée.

In 2022, Nicholas sings Tsarevich Gvidon (The Golden Cockerel) and Harry (Voss) in Adelaide, Handel’s Messiah in Sydney and Adelaide, Jaquino (Fidelio) with the Sydney Symphony and returns to Opera Australia as Almaviva.

Nicholas is the current recipient of the Dame Heather Begg Memorial Award.

About the Companies

Adelaide Symphony Orchestra | website

The Adelaide Symphony Orchestra (ASO) is South Australia’s largest performing arts organisation, with a reputation for vitality, versatility and innovation. Since its first concert season in 1936, the ASO has contributed immeasurably to the vibrancy of South Australia’s cultural life.

Each year the Orchestra brings the joy of music to people all around South Australia through its diverse concert program, along with a comprehensive Learning Program for schools, dedicated regional activity and community performances. The inaugural Festival of Orchestra in 2021 saw the ASO collaborate with a range of artists to present six magical nights of music at Adelaide Showground which attracted over 20,000 people to the event.

ELDER CONSERVATORIUM CHORALE | Website

Founded by Carl Crossin in 2002, the Elder Conservatorium Chorale draws its membership from the University of Adelaide and from the wider community.

The Chorale presents a variety of public performances each year with programs that include a wide range of unaccompanied choral music, as well as major choral/orchestral works in collaboration with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra and the Elder Conservatorium Symphony Orchestra. Such collaborations have included Beethoven’s Symphony No 9, Britten’s War Requiem, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Handel’s oratorios Israel in Egypt and Messiah, Bach’s Johannes Passion and Matthäus Passion, Tippett’s A Child of Our Time and Requiems by Brahms, Verdi, Mozart, Fauré and Duruflé. Together with the ASO, the Chorale gave the world premiere of Ian Grandage’s ANZAC memorial work Towards First Light in 2015.

The Chorale has also performed to critical acclaim at national conferences of the Australian National Choral Association and the Australian Society for Music Education.

Carl Crossin Founder, Artistic Director & Conductor

Karl Geiger Repetiteur

Graduate Singers | Website

Graduate Singers, or ‘Grads’, is "one of Adelaide’s finest choirs" (The Advertiser) and has been a dynamic member of the vibrant local choral music scene for over 40 years. Directed by Karl Geiger since 2012, thoughout its history Grads has received critical acclaim as an exponent of fine choral music, and enjoys a reputation for high standards of excellence throughout every aspect of presentation and performance.

Grads is committed to presenting high quality, accessible, and diverse concerts, keeping the choral tradition alive and fresh. Grads prides itself on its versatility, being equally at home with large-scale choral standards as with intimate chamber works.

In addition to presenting its own concert series, Grads regularly collaborates with the Elder Conservatorium Chorale and Adelaide Symphony Orchestra for large-scale choral works – most recently, Carmina burana, and the world premiere of Richard Mills’ Christmas oratorio Nativity. In March of 2021, Grads formed part of the massed chorus for Adelaide Festival’s critically acclaimed performance of Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time.

Performance Images

Most of the images in the performance of Prayer for the Living have been sourced from the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), with the support of Australian Red Cross.

Red Cross is guided by seven Fundamental Principles of Humanity, Impartiality, Neutrality, Independence, Voluntary service, Unity and Universality.

It seeks to prevent and alleviate human suffering and makes no discrimination as to nationality, race, religious beliefs, class or political opinions.

Australian Red Cross’ purpose is to bring people and communities together in times of need and build on community strengths. They do this by mobilising the power of humanity.

In South Australia, Red Cross provides a variety of services to support people experiencing hardship or crisis, including those who are older and live alone, people in the justice system, asylum seekers and refugees, and those caught up in disasters. Please take the time to visit the Red Cross stand located in the foyer or visit redcross.org.au to learn more about their work.

A Sustainable Festival

Adelaide Festival is proudly Carbon Neutral and you can help us reduce our impact on the environment further! Download the Reforest app to track your carbon footprint and plant trees in local reforestation projects to counteract your emissions.